Amongst the “avant garde” revolutionary intellectuals, the situationists were one of a kind. Though they were few, they often were waging battles under the leadership of a young Guy Débord to surpass other contemporary movements such as letterism and surrealism.

Quoting Carlos Granés about situationists: “in a society that annihilates adventure, the only adventure is to annihilate society”. With such an overwhelming enterprise in mind, it is not surprising that this avant-garde group quickly suffered from their own contradictions, for their fondness of purges and procrastination rather than practical action. However, their intellectual footprint in the arts, politics and urbanism has filtered through to our times, through movements like the Spanish 15M or America’s “Occupy”.

A study on situationist thinking quickly reveal a broad comprehension of the implications of scientific and technical progress and their possibilities for the well-being of people. Young situationists show an acute sensitivity towards the problems of their generation (e.g. boredom, alienation by industrialization and its urban consequences, etc) and reckognize the both the unability of current artistic disciplines (including architecture) to properly respond to those challenges, and the engineers’ lack of understanding of the consequences and possibilities of their inventions on the political and social front.

In the times of rising inequalities, of unprecedented urban growth and of all-mighty Amazon, and more than six decades after their first editorial note, the vision that situationists cast on arts, urbanism and automation still holds, as the texts that we have selected for our readers show.

A Bit of History

In short, situationism is heir of three of the main counter-cultural movements appeared on the first half of the 20th century. It all started in 1916 in Zurich, at the noisy and gloomy Cabaret Voltaire, where a small group of artists and irreverent intellectuals around Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara decided that humans had to get rid of the unsupportable cultural, religious and political burden that had brought World War I. Without rules, memory and logic, everything had to be created from scratch, as if men were just forgetful children.

When dadaism gave signs of agony, in 1924 André Breton launched the Surrealist Manifest. Surrealists think and express themselves with the “unconscious”, skipping reason in favour of emotion and intuition. Buñuel, Dalí, Aragon, Man Ray, De Chirico, to name a few, all took surrealism to its peak through the ensemble of arts. But, after the golden age of surrealism during the 30s, a young romanian named Isou accused surrealism and dadaism from stagnation and founded, in 1940, the letterism mouvement.

Isou and the first letterists claimed that arts developed through waves, each one having an ascending and a descending phase. Due to them, poetry was at his low by 1940 and had to be completely reinvented to prepare it for the next rising wave, and thus decomposed in its very letters, to start with. With time, letterists would apply this assumption to many fields of culture and knowledge. A young Guy Debord contacted letterists in the early 50s but, unsatisfied with the spiritual derive of Isou, formed his own group, the Letterist International, in 1952.

In 1957, the Letterist International joined with two other avant-garde groups (the International Mouvement for an Imaginiste Bauhaus and the small London Psychogeography Association) to form the Situationist International. The group was tightly controlled by Guy Debord during their most active years (from 1957 to 1968), who fueled intellectually the situationists and established their course through the many ups and downs of the political and cultural milleu during the convulsed 60s.

The Situationist International edited a magazine under the same name. In its founding statement they claimed that it was time to move on from surrealism, now that its techniques had been adopted by reactionary forces. Influenced by technical progress and fascinated by the developments of psychology, early situationists pushed for uniting all arts under the umbrella of Unitary Urbanism. In their vision, the city would turn into an ever changing decor that would make their inhabitants, exonerated from work thanks to technology, live their everyday life following their desires.

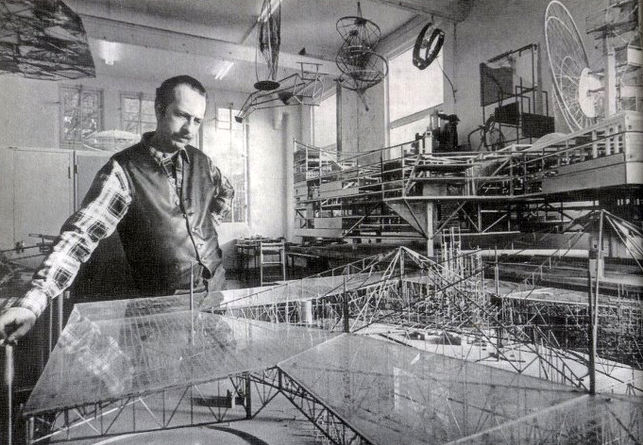

Even if Debord always held the overall vision of situationist thinking, during the first period of the S.I. he commissions urban matters to Constant Nieuwenhuys, a Dutch painter and architect that had founded, a decade before, the CoBrA movement. Constant worked on a practical implementation of Unitary Urbanism through designs of the New Babylone city model. By 1960, an exhibition in Amsterdam on Unitary Urbanism was on its way. Simultaneously, a great dérive (a situation) was to be held through the center of the Dutch capital.

Unfortunately, the Amsterdam exhibition was canceled due to the situationists’ refusal to comply with the requirements of the museum on fire prevention and security, as well as on financing. Soon afterwards, after other disagreements on practical action and strategy, Constant left the group and the whole Dutch section of the S.I. was dismanteled. Subsequently, the task of developing Unitary Urbanism passed in 1960 to the Belgian section of the S.I. in Brussels. Attila Kotanyi, a Hungarian poet, was commissioned to guide the efforts with the help of Raoul Vaneigem.

Kotanyi did very little on Unitary Urbanism other than stop its practical development and, in turn, reaffirm its critical nature. In 1963 he was kicked out, accused of obscurantism, self-interest and laziness.

After 1960, the S.I. progressively evolved towards more political arenas. As the decade avanced, they echoed after-colonnialist tensions all over the world, sympathising with uprising movements all over and (intellectually) paving the way to the events of May, 1968 in Paris.

Although they officially came to a halt in 1972, in practice they ceased all activity in 1969. By then, they considered their influence on the recent May, 1968 events in Paris as their major success. A success that made any prolongation pointless.

Selection of Texts

The following is a selection of situationists’ texts over time. Although most of them are excerpts from the “Magazine of the Situationist International” (from the extensive compilation found at “The Situationist International on-line”), their main publication while the group was active, we have added other texts that complement or update the vision of Débord, Constant and his comrades over the three topics more relevant to city making, and thus to Uerbequity readers: arts, urbanism and automation. Although the “Magazine…” comprises twelve issues, we have restrained our compilation to the first four. They correspond to the period where Constant was included in the group and they reflect a more practical view, especially regarding urbanism. After Constant’s depart, the S.I. takes a more political path, less interesting from a city-making perspective.

Arts and the “Avant Garde”

The invention of Morel. Adolfo Bioy-Casares. 1941. Bioy-Casares’ 7th novel, praised by J.L. Borges and Octavio Paz as “the perfect novel”, it features a fugitive trapped in an island where the same situation repeats endlessly everyday thanks to a machine (invented by a certain Morel) able to capture and display all our five senses. Although we have not been able to find references to this work in the Situationist International, Morel’s machine is clearly a full realisation of the future of cinema, not merely limited to images and sound, that Débord envisions.

The Bitter Victory of Surrealism. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Opening editorial note in which situationists reckon that the adoption of some of the surrealists’ techniques (e.g. brainstorming) by the political and economic establishment, combined with the absence of a revolutionary mass action, means an irreversible degradation of surrealism. Ironically, as we will see through the current selection of writings, many situationist concepts are currently being adopted by counter-revolutionary forces, in which seems to be “a bitter victory for situationists”.

The Sound and the Fury. Paris. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Where situationists denounce the futility of the different “angry young men” protests spreading over Western countries (from England to Sweden), derived from the inmense boredown that youth experiences. A boredom that only situationists (and not “decrepit” surrealism), holding the torch of individual freedom, can turn into a revolutionary force. Half a century later, other “angry young men” flooded Arab plazas in the “Arab spring”, Spanish streets in the 15-M movement, and New York’s main avenues in the “Occupy Wall Street” protests. In the aftermath of this wave of protests, right-wing prime minister Mariano Rajoy replaced social-democrats in Spain, Trump replaced Obama in the U.S.A. and a plethora of dictators (with the sole exception of Tunisie) still hold the power in Northern African and Middle East countries.

Contribution to a Situationist Definition of Play. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. The task of situationists is to stress the values of play (a liberation force) over work (an anihilation force). But not any type of play; only the “disappearance of any element of competition” can revert the act of playing to its original social functions: that is, an exercise of collective action. Today, play as an innovation technique has replaced the surrealist “brainstorming” in many business-related events. On the other hand, some schools are banning competitive sports from their playground activity in an attempt to improve educational environment.

Preliminary Problems in Constructing a Situation. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Situations are composed of gestures inside a transitory decor, and they are set to facilitate the fulfillment of our desires. They must be collectively prepared and developed, led by a producer or director. Passive spectators must be “forced” into action. On the urban front, we have to free ourselves from the automobile (a functionalist toy) and embrace play. We, passive spectators of industralism, must step up as real actors and live life as a continuous collective play that blurs the distance between desire and reality. Two casualties were expected on the way: theater and poetry, as we know it. However, in 2019, both, poetry and theater, are still alive and in good health. In the case of the theater, this good health is visible in the myriads of grass-roots groups of improvisation, which can be considered, with the situationist’s permission, a small and reconforting, though posthumous,”victory of surrealism”. In the case of poetry, youngsters (many of them angry), have developed new bottom-up styles such as rap, a style not entirely empty of situationist traces.

Definitions. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Constructed situation, situationist, situationism (a meaningless term improperly derived from the above. There is no such thing as situationism, which would mean a doctrine for interpreting existing conditions. The notion of situationism is obviously devised by antisituationists ;-), psychogeography (the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behavior of individuals), dérive (a mode of experimental behavior linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances) unitary urbanism (the theory of the combined use of arts and techniques as means contributing to the construction of a unified milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behavior), détournement, culture, decomposition.

Theses on Cultural Revolution. Débord. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Where situationism is defined as participation, passion, abondance, life and inmediacy. And art is defined as an “organization” in charge of producing, not new paintings, nor sculptures, nor music, but people. In this sense, the Situationist International is a sort of trade union whose members are the workers of an “advanced culture.” To be noted that, although Lefèbvre is criticized in this text as a “conformist” because of his renounce to abolish established cultural paradigms, Debord acknowledges that situationists comply to what Lefebvre calls “romantic-communists”, however in an unexpected manner: they can be seen as romantic, not because their endeavour is impossible, but because they are not made to succeed. By anticipating their failure, Debord skillfully sets the framework for a future narrative of succeed.

Action in Belgium Against the International Assembly of Art Critics. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Situationists claim responsibility for an incident in the House of the Press, in Brussels, where a text demanding the cancellation of the event was distributed between attendants. The text claimed that situationists where the sole organizers of the unitary art of the future and, therefore, art critics should “dissapear”. The text is relevant because, ironically, this appears to be one of the few actions that situationists created during the decade that the Situationist International was active.

On Our Means and Our Perspectives. Constant. Magazine of the International Situationist #2. Dec 1958. This article is both about machines (reviewed in the automation section) and about arts. On the arts front, it considers both painting and litterature as dead ends, and therefore unacceptable. Even the renovation of these arts should not be supported by situationists. On the contrary, they must invent “new techniques in every domain, visual, oral, psychological, in order to unite them later in the complex activity unitary urbanism will engender.”

The Meaning of Decay in Art. Editorial note. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Dec 1959. Where situationists reckognize that, although all forms of artistic expression must end prior to finding new and superior ways of communication in a classless society, maybe that doesn’t imply their inmediate dissapearance. They seem to suggest that some artistic expressions can be saved, in the interim. If, as stated in this text, “the culmination of a poem is the silence”, or “there will be no art separated from life because life itself will be a style”, then there must be some room between the revolutionary art for musical expressions like John Cage’s 4’33”. In light of this conception of life as an artwork, how not to think about the essay by Sarah Blackwell on Montaigne: “How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts”.

Discourse on Industrial Painting and a Unitary Applicable Art. Pinot-Gallizio. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Dec 1959. Where a new path (the only possible one) is explored if painting is to be saved and included into the “unitary art”: this is painting performed by machines. Industrial painting makes the work worthless (in the monetary sense of the term) and expands art’s reach endlessly. It is not difficult to find ressemblances between these postulates and Ikea’s paintings or popular reproduction of Warhol’s iconic works, to name just a couple of contemporary examples of devalorisation of art. In terms of architecture, Pinot-Gallizio notes that all permanence should be excluded from the unitary art, hence the only field for architects is to create urban decors. These should be constantly changed and renovated to follow people’s desires and inspire joy (such in an amusement park). It is hard not to find similarities with today’s experiments with techniques such as video-mapping, able to awesomely change the way buildings and monuments appear.

Urbanism (and Psychogeography)

Formulary for a New Urbanism. Chtcheglov. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. (First published at the Letterist International, by Gilles Ivain in 1953). What is the outcome of a mechanized civilisation? Boredom. Against it, mobile decors must be invented. The cold architecture of today must change and design evocative buildings. Buildings that change with nature and respond to the citizens’ desires. In what is a first approach to a “hacker ethics” and “open source” vision into urban design, this new urbanism will lead to an experimental civilisation living in reconfigurable cities producing vast amounts of knowledge. Sentiments will be mapped in the different districts of the city of the future, evoking play and amusement even when approaching to their darkest zones (as the “tragic quarter”, a Tim Burton’s precursor in the sense of a certain playful view of shadows and death).

Venice has Vanquished Ralph Rumney. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. The first article of the Situationist International about psychogeograpgy never arrived on time. Its author, a young Ralph Rumney, founder and only member of the London Association of Psychogeography, was “swallowed” by Venice and its night life. As a result, Rumney was abruptly expelled from the group. He continued a life of a wanderer, marrying Pegeen Guggenheim (the daughter of Peggy Guggenheim) and leading an experimental life with few material attachments (he would also marry in 1974 Debord’s first wife, Michelle Bernstein). In that sense, although he almost never belonged in the Situationist International, he was probably one of most coherent situationists until his death in 2002. His thoughts and ideas about psychogeography are published in the book The Map is not the Territory. with Allan Woods (2001).

‘Provisional Demos: The Spatial Agency and Tent Cities’. Mabel O. Wilson. Borders Elsewhere, Oslo: Oslo Biennale and Lars Muller, 2016. If in the projected city of situationists (Deriville or New Babylone), neighborhoods are shaped and named after sentiments (e.g. the “tragic” quarter), Martin Luther King Jr.’s posthumous project, Resurrection City, echoed psychogeography by adopting similar patterns for naming its different parts (e.g. “funk city” or “soul city”). Nevertheless, while situationist urbanism had a utopian character and thus impossible to materalize (New Babylone was an ideal city favouring encounters constructed on top of a set of pillars), Resurrection City succeeded in developing the sense of agency in the dispossesed by means as simple as mere tents. It is unclear whether Debord paid much attention to Resurrection City in 1968, the very same year when he was celebrating the triumph of situationists after the events of May 1968 in Paris.

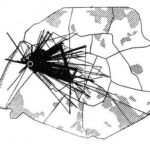

Attempt at a Psychogeographical Description of Les Halles. Abdelhafid Khatib. Magazine of the International Situationist #2. Paris, December 1958. In is work, Khatib develops new means (apart from the “dérive”) to carry out psychogeographical studies: “the reading of aerial views and plans, the study of statistics, graphs or the results of sociological investigations, are theoretical and do not possess the active and direct side which belongs to the experimental dérive. Nevertheless, thanks to them we can arrive at a first representation of the environment under study. In return, the results of our study will permit imbuing these cartographic and intellectual representations with greater complexity and richness”. After Ralph Rumney’s failed attemp, this study is the first psychogeographical work included in the magazine. Thanks to direct observation and manual data collection, Khatib depicts in a map the internal main corridors of the Parisan Les Halles, as well as its real frontiers, which is clearly a prelude of today’s representations of urban life through data visualization.

Theory of the Dérive. Guy Débord. Magazine of the International Situationist #2. Paris, December 1958. In this article, Débord depicts the goals and practical implementation of a dérive, defined as the act of drifting through the city in order to gather data that could later be used to build the psychogeographical maps of the urban networks. These psychogeographical maps are the ‘navigation charts’ of the city. They visualize currents and boundaries, as well as vortexes drawn by attractions of the terrain. All separated by perceived distances (which are different from physical distances). The collected data from these dérives will be, in Debord’s words, the new poetry, capable of inspiring sentiments like rage or joy.

The Image of the City. Kevin Lynch. The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge (MA). 1960. In this fundamental guide for city design, Lynch argues that people “read” cities by constructing mental maps composed of paths, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks. In a way, these five elements do not differ much from the currents, boundaries and vortexes described by Debord’s theory of the dérive. Lynch also shares a common view with situationists when he writes that “there is some value in mystification, labyrinth, or surprise in the environment”.

Cómo los datos urbanos nos revelan la vida oculta de las ciudades. Daniel Sarasa. Urbequity.com. Zaragoza, November 2019. Starting at Chombart de Lauwe’s primitive map of Paris itineraries in 1952 (included in the first issue of the Situatonist International as a last minute fix of Rumney’s map of Venice), the article shows examples of latest attemps to build a new geography based on automatic data collection, and some of its applications.

The Amsterdam Declaration. Constant, Debord. Magazine of the International Situationist #2. Amsterdam, November 1958. The declaration contains eleven statements: eight of them on (unitary) urbanism, one of them on culture, one on automation and one about the organization of the Situationist International itself. Unitary urbanism is the “minimum” program of the situationists, and it can only be achieved through a creative collective effort, in which scientific and artistic methods are applied. Housing, recreation and mobility in cities can be solved through a combined synthesis of psichological, artistic and social perspectives into new lifestyles.

Unitary Urbanism at the End of the 1950s. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Paris, December 1959. Fixing its official born date in 1956, in Turin (Italy), it defines Unitary Urbanism (UU) as a critique (as opposed to a doctrine), as a R&D program in wich theory cannot be separated from practice, and as a radically holistic matter in which no discipline (urbanism, arts or sociology) can be contemplated in isolation (nor tolerated). UU is central to the situationists, and will develop its goal of constantly transforming cities in permanent quest of urban adventures thanks to the use of the dérive (defined above). The dérive, which is both a means of study and a game, is rooted in Thomas De Quincey’s wanderings over London at the beginning of the 19th century.

Discussion on an Appeal to Revolutionary Artists and Intellectuals. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Paris, December 1959. The importance of this text is that it documents in total transparency a growing dissent between the Amsterdam’s section of the S.I. (led by Constant) and Débord’s group. At the center of the disagreement is the focus of the revolution that situationists strive for. While Débord argues that the S.I. must pursue the political and social revolution, as utopist as it may be, Constant is in favour of shielding the S.I.’s activities from a potential failure by concentrating in the practical achievement of the Unitary Urbanism (UU). The First Proclamation of the Dutch Section of the S.I., in the same issue of the magazine, illustrates the great importance that the Dutch section gives to UU as the new overarching art. The divergence of both positions would provoke, later, the expulsion of Constant’s group, and the subsequent turn by the S.I. towards more political arenas.

Situationist Theses on Traffic. Debord. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Paris, December 1959. Where Debord impels to reconsider the car’s role as the center of modern urbanism due to its character of alienating machine. Instead, he argues in favour of car-free zones at the historic center of cities, a path that started London more than a decade ago. Other Spanish cities followed, like controversial “Madrid Central” or the recently approved Barcelona’s “Low emissions zone”, Europe’s largest area of traffic restrictions for highly-polluting vehicles.

Another City for Another Life. Constant. Magazine of the International Situationist #3. Paris, December 1959. This text constitutes the first attemp to establish some practical guides to Unitary Urbanism. Constant critics the “Garden City” as an alienating machine made for the car and against people, and depicts the new city as a suspended set of buildings isolated from traffic. He also advocates for experimentation with ambiance technologies (sound, odours and lightning) to create new psychological ambiances. We must note here that today’s most succesful shopping centers, such as Intu’s Puerto Venecia in Zaragoza (one of the largest shopping malls in Europe), master these techniques envisaged by situationists 60 years ago. As the situationists themselves said about surrealism when surrealist techniques (such as the brainstorming) were adopted by the forces of capitalism, it’s a bitter success for situationists.

General Description of the Yellow Zone. Constant. Magazine of the International Situationist #4. Paris, June 1960. Constants pursuits here his attempt to build a practice of Unitary Urbanism. After describing its principles in the previous text, he sketches a first practical implementation of the Yellow Zone, an area of New Babylone, the ideal city of UU. Although only roughly, he describes materials (nylon for surfaces and metals for furniture), ambient techniques (mostly artificial), distributions (dwellings, technical services, laberynths, circus, play areas…), and access (underground, car, airplane, lifts…)

Automation and Information Society

The Struggle for the Control of the New Techniques of Conditioning. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. Where situationists reckon the progress of and possibilities of applying andvanced psychology techniques to model or condition human behaviour and, at the same time, they warn against the use of these techniques only by counter-revolutionary forces. This, as other texts in the magazine, is a wake up call for “revolutionnaires” to pay close attention to the new scientific experimental discoveries and use it for liberation purposes. Psychology can help the working class, it says, to “forget” everything, throwing away the heavy social and cultural burden and enter a new phase where everything is permanently reinvented and new.

The Situationists and Automation. Jorn. Magazine of the International Situationist #1. Paris, June 1958. In this mind blowing article, Jorn opens new angles on automation. He opposes the general opinion between intellectuals and sociologues against automation by highlighting its liberation potential. Indeed, if one of the situationists’ motto was “never work!”, what is the problem with robots taking up our working time? In fact, Jorn says, socialism, whose main pursuit is to create material abondance for everyone, should embrace automation with joy. The problem, states Jorn, is that engineers (especially the youngest ones) lack enough culture to understand what is really at stake with automation. The goal is not to turn men and women slaves of robots, but their masters. And to organize our free time in true liberating ways. If in every person there is a sleeping creator, the challenge is to use automation to wake it up. In current times, the debate about automation is central to our economies and politics, and Jorn’s arguments have not yet been surpassed. Ideas such as the need of a “robot tax” that compensates for the loss of working time could effectively have an impact in a more equal income distribution as a result of increasing automation and thus protect the socialdemocrat wellfare state. Because, acknowledging that automation is having the effect anticipated by Jorn in the sense that it increases the general accesibility of products for the majority, it does not close the inequality gap. On the contrary, since in our capitalists societies automation is led by private corporations, the effect is just the opposite. Robots divide the working class in two: those that control, program, repair or invent them, and those who are replaced.

On Our Means and Our Perspectives. Constant. Magazine of the International Situationist #2. Dec 1958. “The machine is an indispensable model for all of us, even artists, and industry is the sole means of providing today for the needs, even aesthetic ones, of humanity on a worldwide scale” […] “Those who scorn the machine and those who glorify it display the same inability to utilize it.”

The Planning Machine. Evgeni Mozorov. The New Yorker. New York, October 2014. In the early 70’s, in the socialist Chile of president Salvador Allende, the project Cybersync attempted to create a public-owned platform with similar traits to today’s Amazon, capable of predicting demands in the whole supply chain network of goods throughout the country. The text complements Asger Jorn’s vision on the pursuit of automation by socialism with a little-known real project. It’s author, Evgeni Mozorov, is a thinker that regularly writes about dangers and concerns of increased privatization of digital services and technology.

Gangland and Philosophy. Kotanyi. Magazine of the International Situationist #4. Paris, June 1960. Although this is mainly a text about urbanism (‘gangland’ is the slang word for some neighborhoods in Chicago ruled by gangs), Kotanyi expresses here an antipatory view about how big data can help us understand cities by noting that “If we were allowed to monitor, by means of an exhaustive survey, the entire social life of some specific urban sector during a short period of time, we could obtain a precise cross-sectional representation of the daily bombardment of news and information that is dropped on present-day urban populations. The SI is naturally aware of all the modifications that its very monitoring would immediately produce in the occupied sector, profoundly perturbing the usual informational monopoly of gangland”. The point for a more decisive intervention of public (democratically elected and controlled) bodies on the issue of data collection and analysis is, therefore, made.

A final note: already in #2 of the Situationist International magazine, we find the following text about intellectual property: “All texts published in Internationale Situationniste may be freely reproduced, translated and adapted, even without indication of origin.” It was 1958 and these people had already invented copyleft, in its most radical version. They left other absolute freedom to publish situationists’ texts, totally or partially, with or without attribution, with the sole exception of their own names. It wasn’t until 1984 that Richard Stallman decided to apply these very same principles to software. Stallman is widely recknognized as the inventor of copyleft and GNU Public License (GPL), which he applied to software, but maybe Debord and his friends should also get some of the credit.

I am not as avant-garde as Debord, but I also think that ideas should be freely used and spread. That is why this article, like the rest of this blog, is published under a Creative Commons license. Some rights reserved.